David Remnick has confessed a couple of secrets about his own writing that most certainly has aroused author envy.

The first is that Remnick doesn’t get writer’s block. The second is that—wait for it—he loves to write. That second confession sounds very surprising since some of the most prolific among the published profess slavery to their craft. (They have to write; they must write!)

Which is why the Pulitzer Prize-winning author was probably bewildered when he made the leap to editor-in-chief of The New Yorker in 1998. From the other side of the desk, a new consciousness developed within him.

“One of the most difficult aspects of trying to become an editor was trying to understand other writers, and help them, encourage them, push them,” Remnick told an NPR interviewer. “I discovered that more writers than I can imagine—and I think they’re being honest—protest they hate writing; they don’t like writing. It’s painful … I didn’t realize it ran as deep, or as wide. Maybe it speaks to the banality of my own writing, or to the limitations of my own writing, but I actually love to do it. I find that the stimulation, and the getting it- wrong and finally figuring out what it is that you think, or the process of making a story out of reality that actually is true, is enormously and endlessly exciting.” And he doesn’t agonize over blank pages. Asked if he gets writer’s block, the author of six books says no. “I just get bad writing,” he says. “Writer’s block means nothing comes out. I haven’t had that experience in any serious way. I’ve had endless frustration. I’ve filled garbage cans, or now we call them bins on our desktops. But I don’t mind the Sitzfleisch necessary for writing, the sort of ass-in-the chair concentrated time. In fact, I relish it.”

***

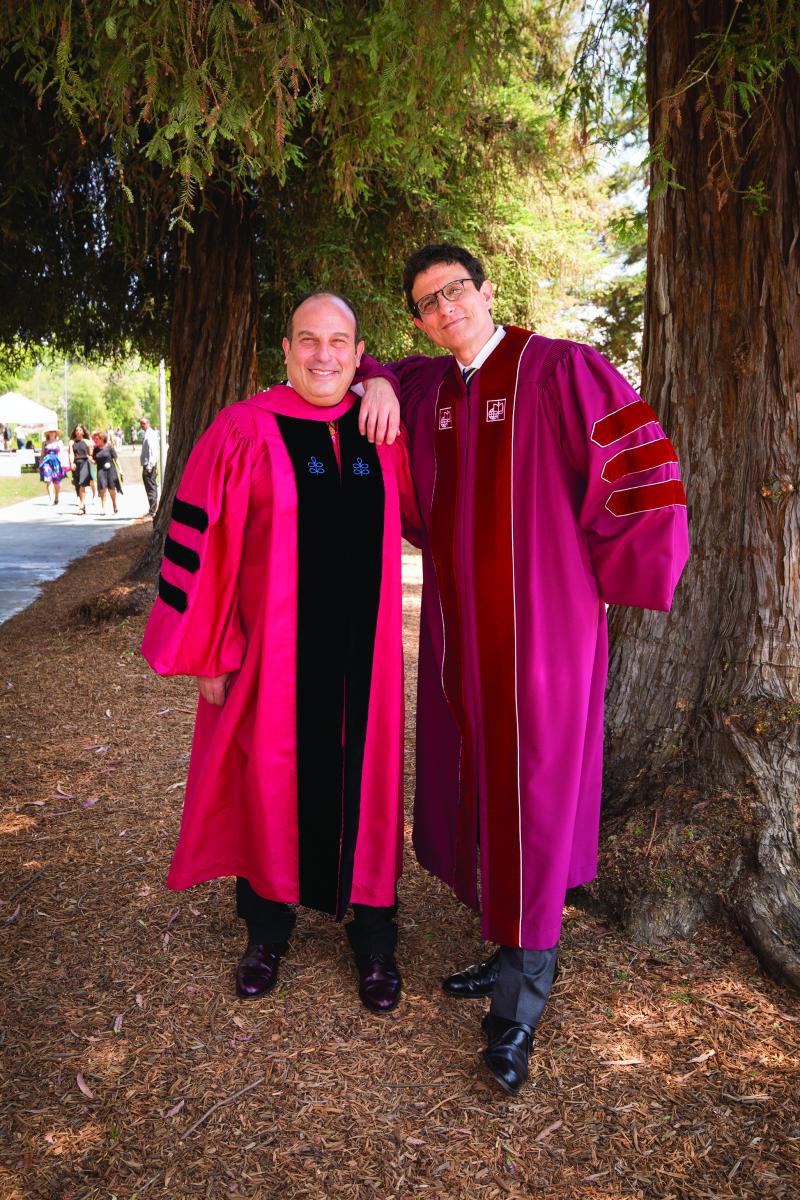

Remnick delivered the 2016 Commencement keynote speech during Claremont McKenna College’s 69th Annual Commencement Ceremony in May.

Addressing graduates, their parents, trustees, faculty, staff and other members of the College’s community, Remnick reflected on his experiences of political protest and dissent as a Princeton undergraduate.

He emphasized how dissent—whether in the form of student protests or much larger civic gatherings—is essential in a democratic nation.

“I have nothing but admiration for students who go about finding their political voices…. Dissent is a large part of the foundation of this country and the movement towards the horizon of a more perfect union,” he told the audience.

***

Remnick graduated from Princeton University in 1981, and worked as a stringer for a local newspaper, taking on obits and whatever stories were offered. “My addiction came early,” he has said of his love for the craft, “and I learned from it.”

Remnick graduated from Princeton University in 1981, and worked as a stringer for a local newspaper, taking on obits and whatever stories were offered. “My addiction came early,” he has said of his love for the craft, “and I learned from it.”

Two big breaks led to his career as a distinguished journalist and prolific expert on Russia: an internship at the Washington Post in 1982 (resulting in his “unbelievably lucky” hiring as staff writer), and the newspaper’s job posting in 1987 for a foreign correspondent in Russia. By then, his interest in the Soviet Union was evident, having studied the Russian language in high school and college. He jokes he landed the job because “Russia is really cold; nobody wanted to be there,” and describes the next four years of his writing career as “the most exalted, least violent, most positive years in the history of the Russian empire.”

Those years would also be the inspiration for his book, Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire (Vintage, 1994), winner of the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction, and a George Polk Award for excellence in journalism. While writing the book, Remnick joined The New Yorker in 1992 as a staff writer and contributed a number of articles, including pieces on Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, Katharine Graham, and Ralph Ellison. Remnick was named editor-in-chief of The New Yorker in 1998.

Although he doesn’t tweet himself, the self-professed “ruthlessly efficient” editor has also expanded the award-winning publication’s digital reach, with an expanded website, app, social media strategy, and— now—radio show and podcast, “The New Yorker Radio Hour.” In 2000, Remnick was named Advertising Age’s Editor of the Year.

In addition to Lenin’s Tomb, he has written: Resurrection: The Struggle for a New Russia; King of the World (a biography of Muhammed Ali); The Bridge (a biography of President Obama); and The Devil Problem and Reporting, collections of his New Yorker magazine pieces. He has contributed to The New York Review of Books, Vanity Fair, Esquire, and The New Republic. He has been a Visiting Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and has taught at Princeton, where he earned his bachelor’s degree, and at Columbia University.

Remnick, whose father was a dentist and his mother an art teacher, says he was raised in the company of books. In high school in New Jersey, he would edit the school newspaper on the family’s kitchen table twice a year. He went on to study comparative literature at Princeton, with the desire to be a writer. However, with ailing parents and “no trust fund” to secure his future, writing books would have to wait.

“Journalism for me was two things,” Remnick has said. “It was a way of seeing the world and traveling, forcing myself to meet people and see other things-- to know something. I’m not a scholar. I don’t have a scholarly temperament.

It was also a way to make a living,” he says.

Stedman is CMC’s former director of media relations and a regular contributor to CMC Magazine and other publications.

To view the entire 69th annual Commencement ceremony, including David Remnick’s remarks, please visit: https://www.cmc.edu/news/cmccelebrates-its-69th-commencement