Our trip taught me how different human life can be. It taught me the value of honesty and the perpetuating destruction caused by corrupt leadership. It taught me the value of fun, and how without it, people lack the drive to do anything. It taught me that without an understanding of joy, there is no incentive to work for it. I believe we gave these kids that incentive.

Tim Storer '15

Our trip taught me how different human life can be. It taught me the value of honesty and the perpetuating destruction caused by corrupt leadership. It taught me the value of fun, and how without it, people lack the drive to do anything. It taught me that without an understanding of joy, there is no incentive to work for it. I believe we gave these kids that incentive.

Tim Storer '15

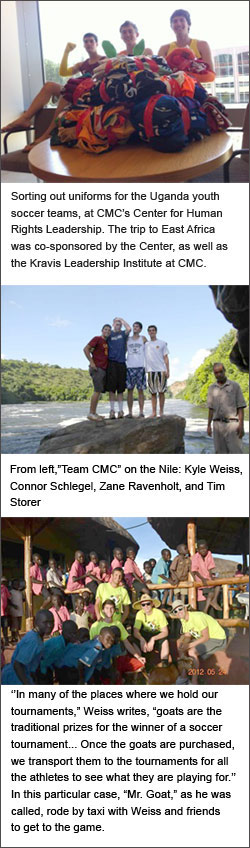

Not long after CMC celebrated the send-off of its most recent graduates, friends Kyle Weiss, Zane Ravenholt, Connor Schlegel and Tim Storer, all rising sophomores, packed their bags for the East African country of Uganda, to host four qualifier soccer tournaments for children under the age of 14. The winning teams would then go on to play a national championship just a few weeks latergames all sponsored by FUNDAaFIELD, a nonprofit that Weiss co-founded with his brother, to develop soccer fields across Africa. (More.)

In their own words, below, the four CMCers recount what it was like being in Uganda, bringing communities together through a sport. Along with sobering moments were the fun and memorable ones riding in a taxi with a prize goat, dancing with children to songs on an iPad, and seeing 1,500 soccer fans cheering the winning players during their victory lap around the town.

Kyle Weiss

Ever since starting FUNDaFIELD when I was 13, I have been exposed to worlds that are completely foreign to your average American teenager. I have wrestled with lion cubs in South Africa, been extremely sick in a small hut in Kenya, and been part of a presidential motorcade in Haiti. These things are hard to explain to people, because they have to be understood in context, and for many people this context is nearly incomprehensible. However, there is one experience that Americans have easily understood: Goats. In many of the places where we hold our tournaments, goats are the traditional prizes for the winner of a soccer tournament. As a result, over the years I have had to purchase my fair share of goats all over Uganda. This sounds like a simple task, but to a suburban American teenager this was about as foreign of a concept as it gets.

It turns out that goat purchasing can be a very delicate task. For example, in Pader, the local tribes are very fond of their goats, so there is a much higher supply of goats and lower prices. In Southern Uganda the volatile weather might mean that a strong male goat could end up costing double the price depending on the season and the geographical region. Additionally, similar to Costco, the more goats you buy, the better. Mix in an exchange rate that compares one U.S. dollar to about 2,200 Ugandan shillings, price discrimination based on my skin color, and a culture with completely different economic policies, and it is easy to understand why things could get complicated.

Once the goats are purchased, we transport them to the tournaments for all the athletes to see what they are playing for. Transportation is not the same as it is in America, and it was not a shock to me, when Tim Storer, Zane Ravenholt, Connor Schlegel, and I found ourselves packed in a Matatu (African taxi) with a very distraught "Mr. Goat."

Although we lamented the fact that "Mr. Goat" would not be spending what could very well be his last hours with "Mrs. Goat," the players' excitement at the prize they could earn made it bearable. When Wagadagu FC won their tournament, they triumphantly hoisted Mr. Goat on the shoulders of their coach and captains, and did a victory lap around the whole town! They were obviously accompanied by the van playing the championship music, and about 1,500 dancing fans. Watching this processional as the sun set over Uganda was only more confirmation to me that we were changing the lives of these kids for the betterin greater ways than we could even articulate.

As best as I can try to paint a picture of this scene, most people will not understand how incredible it was. However to those of us who were there, it was perfect.

Tim Storer

When I first told Kyle I wanted to go on the 2012 FUNDaFIELD trip, I really didn't know what to expect. I knew that there would be cute kids, exotic animals, beautiful scenery, and a chance to do something good for the world, and for me that was enough. While all of these expectations were certainly met, there was one aspect of this trip that really struck me: It taught me the value of fun.

It's easy to think that having fun would be low on the priority list of an impoverished and traumatized nation, but after what we saw, I do not think that's the case. If there is one aspect of Ugandan life that really struck me, it was its mundane and tedious nature. The simplicity of Ugandan life was astounding. While driving around the country, it is common to see people sitting outside. This is not because they are taking a break and enjoying the outdoors, but rather because they don't have anything to do but sit there and watch people pass by. Their schedules are simple, uneventful and repetitive. Furthermore, given the trauma that this country has seen in the past 10 years, the last thing Ugandans need is excessive free time with nothing to take their minds to happier places. More than anything else, the Ugandans seem in need of a good time.

About an hour into our first tournament in Lugazi, I was completely sold on FUNDaFIELD. There was no doubt about itthese people were having fun. A crowd of about 1,500 came out to watch the tournament, mingle with each other, and dance to music (also paid for by FUNDaFIELD). A youth soccer tournament certainly wouldn't draw the same kind of intrigue here in the United States, but for the Ugandans, this was a big deal. It was a means of entertainment, camaraderie, and interest in their lives. The tournament gave them something to talk about for the next week, other than the corruption and poverty surrounding them.

As much as the older people and spectators were beneficiaries of our project, the kids undoubtedly were the primary focus. The players were completely thrilled to participate, and it was awesome to watch them play. From ripping their shirts off to shushing the crowd, the kids loved to do victory dances and cheers. Their fans were into it, too, and had a habit of storming the field after big plays. This tournament matters so much to them that the winners often wear their medals to school for weeks afterward. All this craziness points to one thing: they really, really appreciated what we did for them.

Our trip taught me how different human life can be. It taught me the value of honesty and the perpetuating destruction caused by corrupt leadership. It taught me the value of fun, and how without it, people lack the drive to do anything. It taught me that without an understanding of joy, there is no incentive to work for it. I believe we gave these kids that incentive.

Zane Ravenholt

I was overjoyed when I first realized I would be able to make the trip to Uganda with FUNDaFIELD. I immediately wondered how I might help people there, and what I might gain from the experience. As the departure date grew closer, however, I started to wonder how this group of "leaders" would be able to function without going in opposite directions. The answer turned out to be partnerships.

The first of four soccer tournaments was held in a town several hours outside of Kampala, the capitol. In order to run two tournaments in one day, the students from CMC partnered to run one of them. Only one of us, FUNDaFIELD co-founder Kyle Weiss, had experience running these tournaments. So, of course, he was immediately pulled away for some local resource negotiation issues. Tim Storer, Connor Schlegel, and I were left to organize the teams. Together we handed out jerseys and the identifying wristbands that meant the soccer player fit the "under 13" requirement. Of course, with a first prize goat at stake (and one particularly fleet of foot, as we discovered chasing him down on his great-escape attempt, much to the delight of the laughing villagers) there seemed to be a good number of 13-year-old soccer hopefuls, with the bodies of an 18-year-old. Coaches argued vehemently that these were indeed young kids and demanded they be allowed to play.

We used a means of measuring height and weight to determine age, and because we stuck to it, successfully convinced the coaches to stick to their young players, in general. An X across the wristband attachment was supposed to ensure it was not removed and given to an older player, but occasionally it seemed a young boy would suddenly gain 20 pounds and bust the band. As we kept trying to keep things fair, we also reminded ourselves what a big deal this tournament was for everyone, and how exciting it was for them, as well as for us. We needed to stand firm, but we did so without getting angry about the repeated attempts at rule breaking. And the fun was infectiousso who could blame a coach for trying? What mattered was the joy from the game.

The other tournaments were similar in challenge. Different cultural expectations might lead to confusion or misunderstandings, but eventually the challenges could be solved. Over and over the importance of partnerships became clear. We partnered with local people for fields and resources, with school leaders to support kids, with each other to pull order out of chaos. We learned to do what needed to be donewhen it needed to be doneand to be open to the surprises along the way.

Connor Schlegel

When I committed to join the FUNDaFIELD group on the trip to Uganda, I was not sure what the trip was going to entail. All I knew is that I had never been to Africa, it was a place that I had always wanted to go, and I trusted Kyle. As we got closer to our departure date, I was still a little unsure exactly what I was doing. I knew that I wanted to help Kyle and FUNDaFIELD in any way possible, and I also knew that I wanted to see if I could make an impact on basic medical needs. While Zane, Kyle, and Tim have all explained a big-picture view of the trip, I wanted to share the experience of my Ugandan home-stay.

Right before our walk to the home-stay house, rain started to pour. It wasn't just a normal rainstorm; it felt like fire hoses were above us. We waited an hour for the rain to stop, then headed on our way. Unfortunately, we were unable to walk due to the conditions, so we hired a local to drive us on motorbikes. It was my first time on a motorbike, and it was not a safe endeavor. Picture three full-grown men (my FUNDaFIELD partner, the local, and myself) on a single motorbike that looked like it was made for a 15-year-old. On the way, the tires spun out many times as they tried to grip the still-soaked red clay. After a few miles of tricky driving, we managed to get to the home-stay safely.

Still recovering from the adrenaline rush, Derek, who was my FUNDaFIELD partner, and I were introduced to our families for the night. The mother brought us to her house, a concrete rectangle with a grass roof. She spoke no English and once we were seated at the table, she seemed to quickly disappear to try to avoid any attempt at conversation. We were left with no guidance on what to do for the 16 hours we would spend there until our pick up. Awkwardly we waited, hoping one of the 14 children who were coming and going would come to our rescue. After 15 minutes, we realized we would have to rescue ourselves.

Derek, nervous and much younger, did not initiate any moves. I decided to walk around and see what we could do. I made a few awkward attempts at conversations and received a lot of confused looks and weird smiles. Then I met one of the kids in the family who spoke about 20 words of English. I asked him to show me around his land. The family grew potatoes, corn, and passion fruit. He showed me the small structures that the kids slept in that were like mud huts with grass roofs. Derek joined us and we headed out to their village.

We walked to a field that the local kids played soccer on. The field was at least a mile away from the house; we didn't follow a road, but paths. I realized that if I became separated from this child, no one in my group would be able to find me, and I definitely could not find my way back to the house. It was a refreshingly scary thought, and something I tried to avoid thinking about for too long. Fortunately, we did not separate, and we made our way back to the house without issue.

Luckily, Derek brought his iPad along. Initially, I didn't think it was a great idea, but it turned out to be a success. It was then that we really connected with the kids in the family. We sat around listening to music and everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves. The awkwardness drizzled away as we made a connection with this family through music.

What was amazing to me is how an incredibly awkward situation vanished with the addition of music. It was the only thing we made a connection through. Although we were not able to communicate through language, we danced around. They taught us dance moves, and we taught them a few. It was an amazing experience, and it was the first time in my life that I was completely out of my element. There was no better way to solve our lack of connection than through music.

My Ugandan home-stay was an amazing experience and one that I will never forget. The people I was with could not have lived a more different lifestyle than I do. Yet, through music, we connected and laughed, danced, and had fun together. I want to thank you all for helping to fund our trip. You have impacted our lives in a way that cannot be explained in words.

Next up for FUNDaFIELD: Kyle Weiss, through a paid internship from the Kravis Leadership Institute, is organizing a celebrity soccer game to raise awareness and funds for the nonprofit. The event, he says, is called Chance to Play 2012. A website promoting Chance to Play is expected to be launched soon.