“Leni Riefenstahl and Albert Speer were changelings, they were slippery, they were survivors.”

— Jonathan Petropoulos

Artists and dictators don’t tend to get along, so it’s not hard to imagine the fear that shot though the hearts of musicians, poets, and painters when the National Socialists seized power.

The collapse of German democracy seems especially dire for a modernist—the sort of avant-garde artist whose work would later be denounced in the infamous “Degenerate Art Exhibition” of 1937.

But according to Jonathan Petropoulos, a historian who is one of the world’s authorities on the Nazi cultural policy, a wide range of artists thought that the arrival of Adolf Hitler could actually be pretty good news for them. Some artists fled, some were persecuted, but others worked with the regime for years, making a kind of unlikely peace.

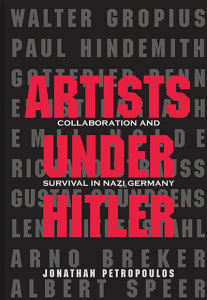

This fascinating, at times queasy and often counterintuitive story is the subject of Artists Under Hitler: Collaboration and Survival in Nazi Germany, which Yale University Press published in November.

This fascinating, at times queasy and often counterintuitive story is the subject of Artists Under Hitler: Collaboration and Survival in Nazi Germany, which Yale University Press published in November.

“I think my book will cut against the grain, and make people rethink their attitudes toward culture in the Third Reich,” says Petropoulos, who is John V. Croul Professor of European History.

The familiar notion that the Nazis hated all modern art—and exalted only thick Wagnerian music or romantic scenes of earnest Aryan peasants—has been revealed as a myth, he says. “What I think is so interesting, especially in the Third Reich, is the gray zone, the gray areas. What’s interesting is the complexity—life and history are never simple.”

The book, which is crisp and readable for the layman, takes a biographical approach, concentrating on ten figures including Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, composer Richard Strauss, filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, and architect Albert Speer. He divides them into two groups—five who sought accommodation with the regime, and five who achieved it. “Each figure is meant to represent a different discipline or field—there’s a musician, a visual artist, and a writer in each category.” Petropoulos wanted artists with engaging and varied stories who were also “representative of something larger.”

His research—much of it in German archives—led him to things he didn’t expect to find. This includes a group of young, modern-minded lovers of Expressionist painting who were nonetheless hyper-nationalistic Nazis. There was even active Nazi support for modernism in Hitler’s early years, and some of the warm climate lingered. “All of the way up to 1945,” Petropoulos says, “there is a vibrant market for modern art.”

Mussolini’s Italy—allied with the avant-garde Futurist movement—showed that fascism and modern art could get along. “All of it gives you a sense of why people like Gropius and [sculptor Ernst] Barlach, who were commendable in a lot of ways, thought they could work in the Third Reich. It was well known that the Nazis were great patrons, and spent money to build museums and buy art.”

Often, his books shows us, the younger artists, more personally pliant and with fewer ties to the old, liberal Weimar Republic, settled more smoothly into the Nazi era. “There may have also been an element of character,” Petropoulos says. “They were able to develop relationships with Nazi patrons and people in power. Riefenstahl and Speer were changelings, they were slippery, they were survivors.”

But it wasn’t just these notorious collaborators, but many artists, across the genres. “Their egos were highly developed and they could not imagine the cultural life of Germany continuing without them. And they believed Hitler and the Nazis were re-energizing Germany.”

Petropoulos ended up concluding—after eight years of research and writing—two things that may sound contradictory. “I’m sure my book will ruffle feathers,” he says. “There are people invested in some of these figures,” including those who’ve written softball biographies. “They’ll find what I have to say difficult. But I’ve tried to be really scrupulous with my research.”

At the same time, he says, sometimes we judge artists who collaborated—especially early on in the regime—too harshly. “We have the luxury of hindsight,” he says. “They didn’t know what was to follow—Kristallnacht, in 1938, which was a real turning point, or the horrors of Auschwitz.”

Petropoulos became involved in scholarship on the culture of Nazi Germany by accident three decades ago, as a graduate student at Harvard who intended to study French. “This topic of Nazi culture reached up and grabbed me.”

Artists Under Hitler concludes a trilogy that also includes Art as Politics in the Third Reich and The Faustian Bargain. Petropoulos has gone as deep into the subject as anyone has, but still sees much in the field that remains rich and unexplored.

“We historians try to make a contribution,” he says. “But there’s still so much more to do.”

Timberg is a former lead arts and culture reporter for the Los Angeles Times. He is the author of the new book “Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class” (Yale University Press).