Video: Looking Back on

20 Years

Through the eyes of the Mgrublian Center for Human Rights' founding leaders, alumni, and students, learn how it has grown into a vital connecting point for so many CMCers these past two decades.

CMC Professor Emeritus and moral philosopher John Roth called it an “oppression-resisting, hope-sustaining, death-defying, life-giving, and joy-creating place.”

Jonathan Petropoulos, the John V. Croul Professor of European History at CMC, called it “the conscience of our campus.”

They were describing the Mgrublian Center for Human Rights, which this year celebrates its 20th anniversary. Roth and Petropoulos were its founders.

From the beginning, the mission of the Center for the Study of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights—as it was initially called—was aspirational in a poetic way:

“To throw light on human rights atrocities around the world” is how Trustee Board Chair David Mgrublian ’82 P’11 described it in a speech he gave April 10, 2015—on the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide—when the Center was renamed the Mgrublian Center for Human Rights. The Mgrublian family created an endowment honoring “the memory of our ancestors who perished.”

Surrounded by his late parents, Harold and Alice P’82 GP ’11, his wife, Margaret P’11, and daughter, Madlyn, David spoke of the “great obligation” the Center’s mission imparts on all of us, saying: “By instilling in our students an understanding of human rights as central to moral conduct and ethical decisions, we are sending [them] into the world to do something about it.”

This call to action is deeply aligned with CMC’s overarching mission to prepare its students for thoughtful and productive lives and responsible leadership in business, government, and the professions and to support faculty and student scholarship that contribute to intellectual vitality and the understanding of public policy issues.

“Our family is incredibly proud of the Center and the important work being done to provide our students with an understanding of human rights that is central to the moral and ethical decisions they will encounter in their personal lives, their careers, and the public arena,” David said.

Doing Something About It

The Center’s origins lie in Holocaust-focused ethics courses taught by Roth, who was a member of CMC’s faculty from 1966 until his retirement in 2006.

It was common for students to approach the popular philosophy professor after class. “We can’t rewrite history,” they would tell him. “We can’t change what happened in the past. But our study is motivating us to want to do something about the world as it exists now, and as it might exist in the future.”

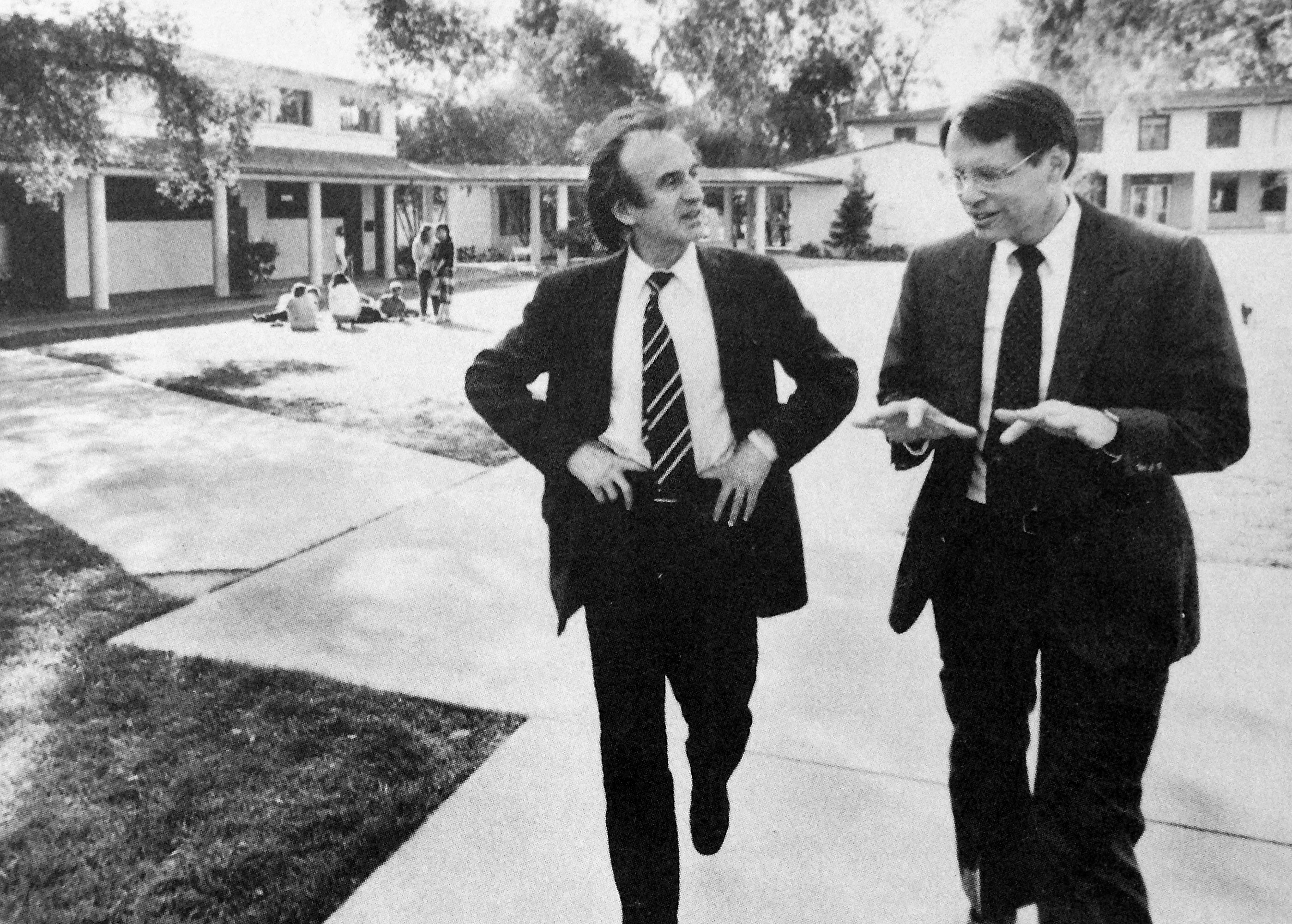

When Petropoulos, an authority on Holocaust art theft, joined CMC’s history department in 1999, he and Roth combined forces to lobby the College’s president, Pamela Gann, for a new Center.

They envisioned a place to study the Holocaust, genocide, and human rights in a holistic way—viewing past atrocities with an eye toward preventing future ones. That idealism set the CMC initiative apart from existing Holocaust museums, memorials, and research centers, which by definition looked backward.

“The hope is, all the study and research will produce deeper answers that can sensitize people and hopefully genocide will end,” Roth optimistically told The Claremont Courier in 2002.

The idea inspired CMC students. In February 2003, one of Roth’s acolytes, Michael Levy ’03, stood outside Collins Dining Hall with a petition asking the administration to endorse the proposed Center. He collected 638 signatures in a matter of hours.

A year later, Leigh Crawford ’94, founder of Los Angeles-based Crawford Capital, provided the necessary founding gift. Crawford became a life member of the advisory board.

Roth and Petropoulos teamed up as the Center’s founding director and associate director in 2003. They tapped some big names for the advisory board, which assured immediate respect and status for the new Center.

Auschwitz survivor and Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel, who passed away in 2016, joined early on. He and Roth were old friends who collaborated on A Consuming Fire (1979), a meditation on the role of Christian theology in the Holocaust. Roth also enlisted UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Mary Robinson for the board.

Meanwhile, Petropoulos recruited star attorney Stuart Eizenstat, an expert on Holocaust restitution law, whom the CMC professor knew through his work on Nazi art theft. Today, Eizenstat chairs the governing council of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and is a special advisor on Holocaust issues to the State Department.

Roth, now professor emeritus, continues to serve on the Mgrublian Center’s advisory board.

When the late Professor P. Edward Haley became Center director in 2008, he persuaded Human Rights Watch, famous for having the most selective internship hiring process, to ink a deal effectively guaranteeing it would take at least one CMC student every summer.

“That was a real coup,” recalled current Mgrublian Center Director Wendy Lower, who in 2014 took the baton from Haley (the emeritus professor recently passed away on June 30, 2023). Other top non-governmental organizations (NGOs) made similar agreements. The Center is crucially committed to covering students’ travel and living expenses, making it possible for CMCers to say “yes” when presented with an unpaid human rights internship opportunity.

At last count, the Mgrublian Center sent 230 summer interns to top human rights organizations, said Kirsti Zitar ’97, who returned to CMC as the Center’s assistant director in 2011. Additionally, it has backed 44 undergraduate research fellows and seeded 13 Best Senior Thesis Award-winning projects in under a decade.

Over the years, the Mgrublian Center has enlisted 136 student researchers, hosted 115 Athenaeum lectures, and awarded eight Elbaz Family Post-Graduate Fellowships. The innovative program, introduced in 2018 and funded by CMC trustee Elyssa Elbaz ’94, provides significant grants to new graduates who secure full-time jobs in human rights.

Today, the Center employs eight research fellows, four legal research assistants, and 17 student assistants, while serving as a connecting point for all CMCers with an interest in hands-on human rights scholarship, research, and activism.

Student-led innovations, such as the Justice League Task Force, keep pushing the envelope of what’s possible.

“In the past two years, our students also started a mentorship program matching CMCers interested in human rights, genocide, and Holocaust studies with alumni or parents currently working in those fields,” Zitar said.

Many Pathways, All Converging

In this respect, the Center remains a unicorn.

“We were among the very first—and still are one of a very few dedicated research institutes—doing human rights, Holocaust, and genocide studies at the undergraduate level,” said Lower, who in 2017 spearheaded the creation of a North American consortium representing some 200 peer programs.

By now, Lower is accustomed to first-year students telling her CMC was their dream school because they see the Mgrublian Center as a springboard for future careers in human rights.

Some have fulfilled that altruistic ambition. Alumni include Oxfam America senior policy adviser Andrew Bogrand ’09 and USAID employees Austan Mogharabi ’07 and Nicole Southard ’17. Mogharabi is director of the federal agency’s Sahel regional technical office; Southard is an information officer with its Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance.

Of course, many Mgrublian Center alumni pursue other paths while continuing to be inspired by what they learned at CMC.

Take Colin Hunter ’05, an attorney with the Angeli Law Group LLC in Portland, Ore. He was among the first to receive a Center-funded summer internship, which sent him to Rwanda to work with an international NGO on genocide memorials.

“That was a life-changing experience in so many ways,” said Hunter, who was active in the Center all through his college years, serving on the student advisory board and co-founding Students Against Genocide (SAG). The Mgrublian Center sponsored the SAG task force’s trip to Washington, D.C., where team members met with State Department officials to advocate for U.S. intervention in the ongoing Darfur genocide and ramp-up relief work in Sudan and Chad.

After leaving CMC, Hunter became a CIA political analyst, focusing on early warning signs of potential humanitarian violations in armed conflicts. He later switched gears, earning a law degree at UC Berkeley. Alongside his civil litigation practice, Hunter continues to work pro-bono on humanitarian issues such as abortion protections and transgender rights advocacy.

“The experiences that the Center created for me inform my legal practice every day,” said Hunter, who stays connected as a Mgrublian Center advisory board member.

The Way Forward

The Mgrublian Center 20th anniversary celebration kicked off in April with its annual Armenian Genocide-focused Athenaeum speaker event, and it will wrap up in late September, with the ImpactCMC alumni dinner. To mark the milestone, the Center is running an Instagram campaign spotlighting “20 faces”—one for each year—among the hundreds who have passed through the Center.

Despite its important work and best efforts, genocide has not been stamped out, as Roth had once hoped.

“There is much that’s dark and dreary about our world, and yet none of that has to be the way it is. Steps can be taken in creative and constructive ways to address those issues,” he said. It’s why the Center is so important 20 years running—and why it must continue to help today’s CMC students see and seize opportunities “to try and change the world for the better.”

“At any moment, we know that somewhere in the world, right now, someone’s suffering—in Ukraine, in China, in Syria,” Lower added. It’s an administrative challenge “just trying to make decisions about where to focus our attention."

Still, there’s reason for optimism.

“The world is getting more interconnected,” Hunter said. “Students have the ability to create content and get it out to millions of people, which we didn’t have back in 2005. I don’t think there’s any limit to what the Center and CMC students can do together.”

In a recent interview before his passing, Haley also pointed out that human rights manifest as a constant problem throughout history. “Our founding of the Center 20 years ago was an attempt to address that aspect of human rights along with trying to understand and derive lessons from the Holocaust,” Haley said. It requires of us all the “opportunity to look back and then to look forward. … to be full of hope and energy and idealism.”