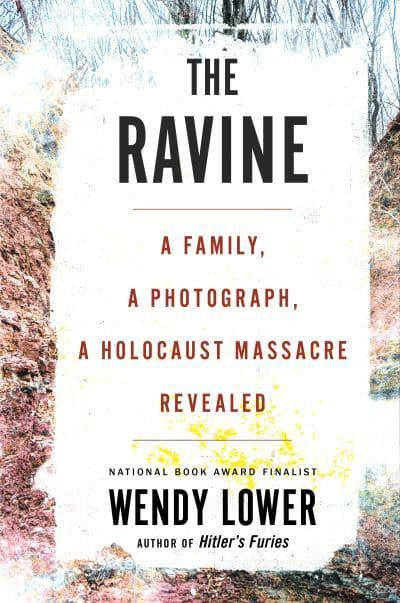

CMC Prof. Wendy Lower’s latest book, “The Ravine: A Family, A Photograph, A Holocaust Massacre Revealed,” reads like a detective story.

Lower begins her compelling first-person narrative in the archives of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum with a discovery of a rare photograph from 1941. The photo depicts the shooting of Ukrainian Jews—a woman and children. Compelled to learn the victims’ identities, and those of their killers, Lower launches an investigation that lasts a decade and leads her to the scene of the crimes in Miropol, Ukraine, with research stops along the way in Israel, France, Germany, and Slovakia.

Published in 2021, “The Ravine” has received praise from around the world. PEN America named it to their Longlist for the 2022 PEN/John Kenneth Galbraith Award, “which recognizes a book of nonfiction possessing literary merit and critical perspective that illuminates important contemporary issues.” The book was also short-listed for the 2022 Wingate Literary Prize and won a 2021 National Jewish Book Award.

Lower is John K. Roth Professor of History and George R. Roberts Fellow at CMC and the director of CMC’s Mgrublian Center for Human Rights. Previously she authored “Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields,” which was a 2013 finalist for the National Book Award.

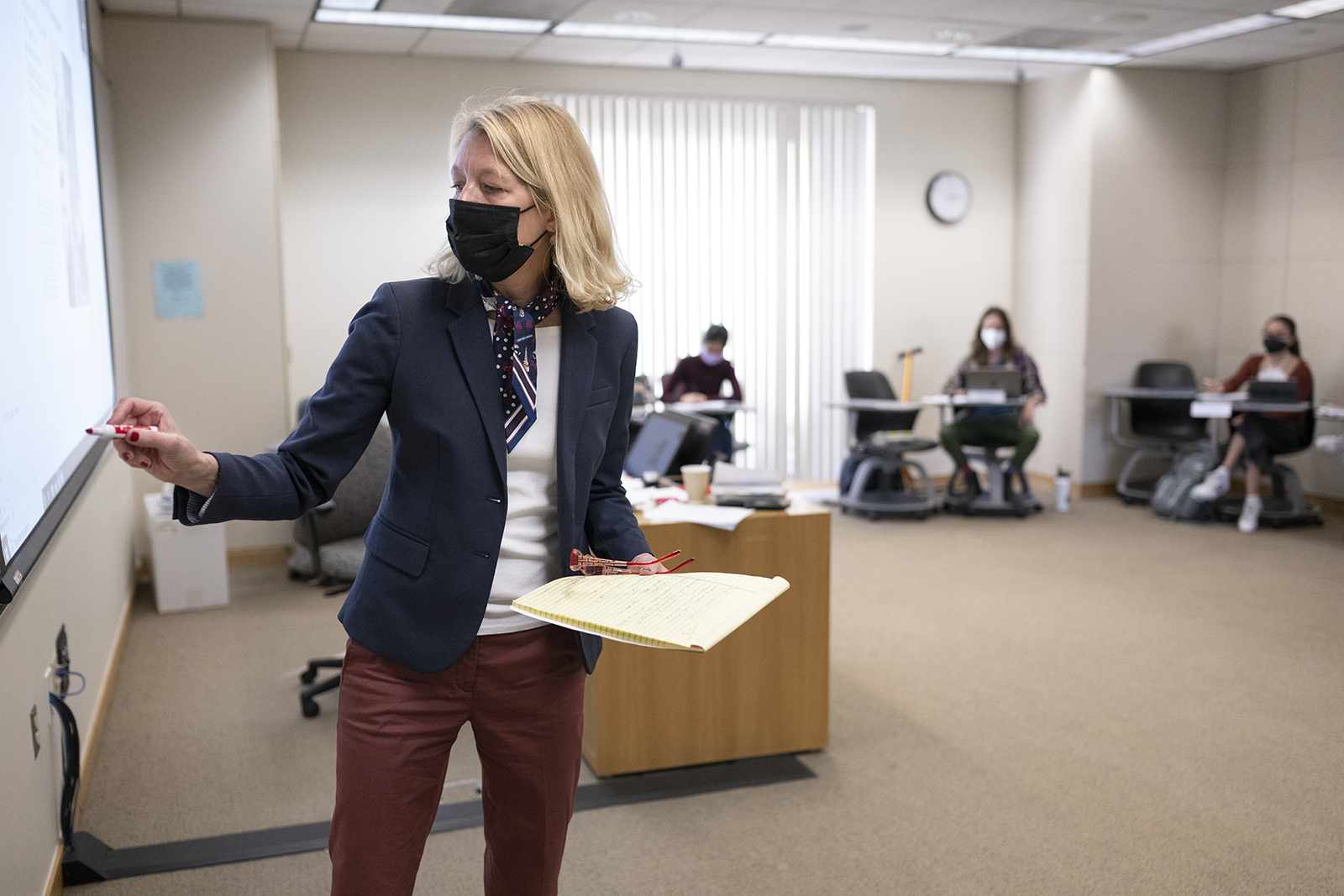

Just outside her office at the Mgrublian Center, Lower recently sat down to discuss the interdisciplinary research methods she deployed to explore this chapter in Holocaust history, tell the victims’ stories, locate the killers, and reveal an unlikely hero—the photographer himself.

As you began to investigate the photograph, how did you shape your approach?

I had written books that privileged the use of Nazi documentation, but for this project, I wanted to explore how visual sources might open up new lines of inquiry and discovery about the Holocaust. This atrocity photograph was part of a series of previously unknown images that were unlike any I had seen before. They were among the most vivid, action shots of Nazi killers and their Ukrainian collaborators murdering Jewish civilians in broad daylight. More than one million Jews were gunned down in ravines, pits, and quarries of Ukraine, and most of these victims—many of them children—have not been identified.

Looking at the photograph raises many ethical issues about the victims. For instance, is this how the victims, the descendants of these victims, and the survivor community, want to be portrayed? Often atrocity images are reproduced, published, and displayed without considering that view. As a historian, I was concerned about the lack of research on rare photographs, including images I had seen of lynchings, which were used as “stock” illustrations but not studied as historical documents. These images may be the only evidence we have of historical crimes and persistent injustices that we need to reckon with today. In the case of the photographs featured in “The Ravine,” they are the only trace of the existence of those victims whose lives were brutally cut short.

What was something that surprised you as you did your research?

The photographer, who was a Slovakian guard attached to the German military forces that invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, turned out to be a really likable, inspiring person. When I first looked at the photograph—as I did, or anyone does when you open the book—you assume certain things, right? But the research is about testing those assumptions, and your own bias.

These victims were experiencing the worst possible moment together. They’re being murdered as a family unit. It’s everyone’s nightmare. Why would someone take a picture of that and further humiliate them? He’s taking the photograph openly because he was allowed to. He said in his testimony after the war, that he was allowed to take it. But what’s interesting is, this isn’t the only photograph. He took seven or eight pictures with the film he had loaded in his camera that day.

In the book, you can see that we found another five photographs. We realized that this was his visual testimony. This is a report of what happened in sequence to show you how the Jews were forced to march there. Then, the last picture is taken looking down into the mass grave. You can see the same woman and children there, lying together.

Snapping these images with his camera was the young photographer’s turning point. He became an active resister and even hid a Jewish family in his attic.

In addition to archival research, your work takes you into the field where you collect testimonies. While it requires patience, can you share with us how doing fieldwork allows you to be more open to what you call, “serendipity moments”?

When you’re out in the world interacting with human beings, you find that someone always has a story to tell. And the Ukrainian peasants I spoke to, certainly did. In this case, it’s fascinating, because you have witnesses who are so far removed from academic discourse, the Holocaust memorial world, and the research institutions and museums that we have, but they remember a particular day or moment when they saw something. Or, they can identify a key detail, such as the color of the German uniforms, not available from the black-and-white photograph. That’s a big piece of information for someone like me, because knowing the color of the uniform, narrows it down to who was involved in the killing.

The peasants also described their struggles before, during, and after the Holocaust in Soviet Ukraine. This helped me fill in the local history beyond the frame of the 1941 photograph.

Can you talk about how your research intersects with other disciplines to tell this story?

Overall, I find that the community of scholars who do this work, do it together.

When I first saw this photograph in 2009, it was brought to my attention by two journalists who had traveled from Prague. It was a classic scene at the museum, where you’ve got a lot of researchers, descendants of survivors, survivors themselves—a whole community of people who are dedicated and trying to kind of get to the bottom of this vexing, horrible chapter in human history.

There's a lot of mutual help. For instance, I don't read Slovakian, so survivors and descendants of some of the survivors from Slovakia, volunteered to help me, and translated many of these documents for me.

I also learn from my colleagues at CMC, in this community of intellectuals, who are working on myriad subjects in the humanities and sciences. We can find research connections in our respective disciplines. A literature professor recommended that I read a poem from a Holocaust victim that I was unaware of, or a psychology professor pointed me to more literature on human behavior. This kind of sharing is essential for raising new questions and finding sources outside of my field.

This is such a serious subject and the photographs are so graphic. How do you keep going? Does this work take a toll on you?

It does, but that’s what also drives the work, the emotional and intellectual aspects. In the images, we see innocent civilians mass-murdered with their families. Their existence and history were obliterated. In genocide studies, scholars try to recover that, explain what happened, and its impact today. Political scientist Adam Jones, William F. Podlich Distinguished Fellow in residence at the Mgrublian Center, established in his massive global history of genocide that it is a phenomenon with deep roots that reemerge in various settings and forms. Yet Holocaust, genocide, and human rights studies are newer fields of study. We have much more to learn, and to do as far as genocide prevention.

Can you tell us about some of the CMC connections who assisted you in this work?

I couldn’t have completed “The Ravine” without access to faculty research funding, which was really decisive.

I also benefitted from the students in my classroom. Often, I shared what I was working on with my students and elicited their feedback, which helped ground the project. They would ask big questions and point out details in the photograph that got me thinking, and revising. In addition, Dunbar Fellow Julie Kim ’17 (funded by the Gould Center) and Lucie Kapner ’22 (funded by the Mgrublian Center) served as my research assistants during the summer and semester breaks.

On the technical side, once I realized that I wanted to produce cut-outs of the photograph and analyze each element, CMC’s IT team provided me with the digital tools to do this, which improved my analysis and public presentations.

Overall, I want to recognize the Mgrublian Center, which is dedicated to these topics and provides me the critical support and infrastructure that I need to accomplish this work.

What’s your next project?

Jonathan Petropoulos (CMC’s John V. Croul Professor of European History) and I are co-authoring a book project on Heinrich Himmler, who was the head of the entire Nazi terror apparatus, and second after Hitler, as far as who was most responsible for the Holocaust. We want to focus on his end. It can be instructive to not always think about these horrible actors in their prime, but rather to explain how it can come apart, how genocidaires can be defeated and how their systems can be dismantled.